AI promised an easier life but an MIT study shows devastating long-term effects. The hard path is where meaning, memory, and soul will live in the future. What do you think?

I've been an AI enthusiast until now. I think 2026 is about to change all of that.

This December marks two years of my tryst with AI. I've tried it for everything relevant to my world: ideation, deep research, writing, generating images and videos, creating avatars and voiceovers. I've built apps that help me create products, deployed AI agents, automated workflows and for the most part, these tools have made my life a bit easier, perhaps even slightly more productive. So I am by no means a beginner.

I've been an early adopter for most technologies. Right now I'm living in the world of Spotify, music summoned instantly from the cloud. But I also still have my cassette tapes. I exist in both worlds simultaneously; the frictionless new and the tangible old. Between those cassettes and this streaming service came CDs, then iPods. Each shift gave me time to adjust, to understand what was gained and what was lost. AI's pace is different. It bewilders me. I'm living in multiple timelines at once and I can't keep up.

While I was experimenting, mainstream content creators had already mastered the use of AI. I started noticing the scaffolding beneath AI-generated text. It had a rhythm to it, a mechanical predictability. The same constructions appeared again and again: "not just X, but Y" to create emphasis. "From ancient traditions to modern innovations" to span time or show scope. Participial phrases tacked onto the end of sentences, as if added by formula. "Whether A or B" presented false choices. "If-then" conditionals hedged every claim.

These and several other patterns emerged not from thought but from probability. The algorithm has learnt what comes next and serves you that. Human variability, the capacity to surprise yourself mid-sentence, was already lost by this point.

I caught myself doing it the other day. Writing an email, I started with 'not just X, but Y' and stopped mid-sentence. Had I always written like this? Or had only a couple of years of reading AI output trained me to think in its rhythms? It's like when you live with someone long enough, you start using their phrases without realising it. Except I'm living with an algorithm.

People wrote more using these patterns. YouTubers created training reels propagating their prompts, sharing their "secret formulas" for getting AI to produce better content. Which only amplified the sameness. The patterns became templates. The templates became best practices. Soon everyone was feeding the same structures back into the system, teaching the algorithms to be even more predictable. We were training AI to sound like AI, then congratulating ourselves for learning how to use it effectively. A closed loop of mechanical thinking, getting tighter with each iteration.

Now everything looks, feels, and reads the same. Watch ten different creators and you're watching the same video ten times. Read ten different articles and you're reading variations on a single template. It's as if we've all hired the same scriptwriter and video editor, then convinced ourselves we're still making original work.

But something deeper was bothering me, something I couldn't yet name. Every time AI made something for me - an image, a piece of music, a paragraph, I felt a strange hollowness. The output was there, but something essential was missing. I would later come to understand this as the soul question: What do we lose when we outsource the parts of creation that feel hard? What happens to us when the struggle itself disappears?

Given our shrinking attention spans, I thought these patterns were forgivable. Everyone was doing it. Then I heard Steven Bartlett talk about why he's quitting AI. He mentioned a study by Nataliya Kosmyna at MIT Media Lab, a 20-page technical preprint combining neuroscience, behavioral analysis, and computational linguistics to investigate how AI tools like ChatGPT affect brain function during essay writing.

The study hasn't been peer-reviewed yet. But I couldn't ignore what it found.

The researchers compared three groups of students writing essays over four sessions spanning months: one group using no tools, one using search engines like Google, and one allowed full access to ChatGPT.

ChatGPT users showed about 47-55% less brain activity in areas linked to thinking, planning, memory, and creativity. The EEG scans revealed the weakest brain connections, especially in slower brain waves. Search engine users fell in the middle. The no-tool users had the strongest, most connected brain activity.

The memory findings stopped me cold: 83% of ChatGPT users couldn't remember or quote their own essays right after writing them. Almost perfect recall in the no-tool group. And this gap didn't close over time…it persisted even after months.

Then there was the ownership problem. AI users felt their essays were less theirs; many said only 50% or less was their own work.

The study identified signs of what it called "cognitive debt." Over time, heavy ChatGPT use seemed to make people put in less mental effort. The more they relied on it, the shallower their thinking became and in the long run, switching away from AI proved hard.

Sure, ChatGPT makes essay writing faster and easier. But when used heavily, especially for core thinking and writing, it reduces active brain engagement, weakens memory, lowers originality, and may slowly erode cognitive skills. The researchers suggest it's like taking on debt: you get short-term gains but pay heavy interest and fines later, in reduced mental sharpness. They recommend using AI sparingly and prioritizing unaided work for real learning.

With our attention spans already shrinking, the fact that we might be developing memory worse than a goldfish felt scary. Until this point, I had primarily used AI as a research assistant. After discussing an initial idea, I would ask for a comprehensive reading list and still go do my own reading. If I'm researching for a book, I continue making handwritten flashcard notes like Ryan Holiday does.

The MIT study made me realise that even essay writing, something demanding, had been reduced to what Cal Newport would call shallow work. Newport's Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World has been a useful guide for me.

Newport defines deep work as professional activities performed in distraction-free concentration that push cognitive limits to create new value, improve skills, and produce high-quality output that's hard to replicate. Shallow work includes logistical, easy-to-replicate tasks like emails, meetings, and administrative busywork that don't require intense focus.

Newport argues that modern technology, particularly network tools like email, Slack, social media, and instant messaging, pushes knowledge workers towards shallow habits by fragmenting attention, rewarding busyness over depth, and exploiting human psychology.

His warning is structural: Tech isn't neutral. It carries within it economic incentives that push us toward shallow habits. Platforms profit from engagement, from keeping us scrolling, clicking, reacting. The more our attention fragments, the more valuable we become to advertisers. What began as a business model has now become deeply ingrained a cultural norm.

So much so, that we have stopped noticing that we can't focus anymore. We accept that deep work is a luxury, something you do on weekends or when you have time. The skill becomes rarer precisely as its value grows, because everything around us is engineered to make it harder.

The MIT study wouldn't leave me alone. Students who couldn't remember their own essays and brains with 47-55% less activity. As the machines keep getting smarter, humans keep getting dumber, I wondered if this is what AI does to individual minds in a few months what does it do to a civilisation over time?

I thought surely others were talking about this. Surely someone with a helicopter view is flagging this as an issue or a risk in the longer run? Sure enough, they were. In fact, until now I had no idea this had been identified as an extinction-level problem! I had resisted going down this rabbit hole for the fear of having to confront the truth of my own use of AI. This time I voluntarily jumped in and explored.

I began to realise that the same mechanistic thinking that erodes individual cognition at the personal scale is now driving reckless development at the species scale. When you treat human attention as a resource to extract, when you see thinking as inefficiency to be optimised away, you don't stop at making individuals shallower. You build systems that treat human judgement itself as an obstacle.

These decisions come from the same place: a refusal to ask whether the thing we're optimising for is worth having. We're so focused on how fast we can go that we've stopped asking where we're going.

Stuart Russell, the UC Berkeley computer science professor who wrote the standard AI textbook, has spent decades working on how to keep advanced AI under human control. Time magazine calls him one of the most influential voices in AI, and he directs the Center for Human-Compatible AI. When someone with his credentials warns about extinction risk, I listen.

Russell describes a small group of AI companies racing to build AGI, artificial general intelligence that can match or exceed human capabilities across all cognitive tasks. He talks about the "gorilla problem": humans are so much smarter than gorillas that gorillas have no say in whether they continue to exist. We could wipe them out in weeks if we chose. As we create something more intelligent than ourselves, his worry is simple: we become the gorillas.

But what disturbs me most is not the technical risk. It's the lack of agency, the stolen choice. A handful of CEOs at OpenAI, Anthropic, Google DeepMind, and a few others are pursuing what Russell calls a "15 quadrillion dollar prize," a system that could replace all human labor and capture almost unimaginable economic value. These same leaders publicly acknowledge non-trivial probabilities of human extinction from their work. Yet they proceed anyway, playing Russian roulette with every person on Earth without asking permission.

I never consented to this bet. Neither did you. Neither did the billions of people whose lives hang in the balance of decisions made in San Francisco boardrooms. A civilisation-scale project with civilisation-scale risks is being driven by a few actors who stand to capture nearly all the gains while everyone else bears the danger. We have no voice, no agency, no control.

In October 2025, around 850 experts, including Russell, Geoffrey Hinton, and Richard Branson, signed an open letter calling for a ban on superintelligence development until there is broad scientific consensus on safety and strong public buy-in. The fact that such a letter exists, that some of the most knowledgeable people in AI are sounding alarms, should tell us something. The fact that most people haven't heard about it should tell us something else.

Another alarm bell I'd heard recently, rang again. Paul Kingsnorth's Against the Machine delves into deeper, more spiritual and philosophical questions. Kingsnorth talks about modern "machine" civilisation as an inhuman, spiritually dangerous system tightening around us through technology, capitalism, and a specific way of seeing the world.

This way of seeing is a modern, mechanistic, utilitarian outlook that treats the world as a collection of parts to measure, manage, and optimise, rather than as a living whole filled with meaning. It reduces people, places, and nature to resources, data points, or problems to be solved, instead of relationships to be honoured or mysteries to be lived within.

Kingsnorth proposes four traditional anchors of human life that are being uprooted: people (community), place (embeddedness in nature and locality), prayer (relationship to the divine), and the past (living within a tradition). He argues that modern machine culture systematically uproots all four and replaces them with consumerism, ideological progress, and technological systems that promise improvement but erode meaning and belonging.

I felt this personally. My relationships feel shallower, more digital, less embodied. I message more but connect less. I can work from anywhere, which sounds like freedom but feels like rootlessness. I belong to screens, not to soil. My sadhana has become inconsistent, crowded out by the urgency of shallow tasks. The wisdom of elders feels quaint, almost irrelevant, when the world changes faster than they can advise.

These four anchors map onto something I already know: the purushartha framework from my own tradition. Dharma (righteous path), Artha (prosperity), Kama (desire), Moksha (liberation). The framework assumes all four aims are legitimate and necessary, but Artha must be pursued within the guardrails of Dharma. Wealth without righteousness is dangerous. Profit without moral constraint is destructive.

This is precisely what's happening with AI. The companies Russell names are chasing Artha [the 15 quadrillion dollar prize] without Dharma guiding the pursuit. They acknowledge extinction risks but proceed anyway because stopping would mean losing the race, losing the profit. The framework has collapsed. Artha operates alone, uprooting Kingsnorth's four anchors in its path.

Whether the purushartha can help us answer the questions Newport, Russell, and Kingsnorth raise is my contemplation for 2026. But I suspect it can, because these are not new questions.

I now have the vocabulary to voice the dichotomy I've felt recently. AI is hollowing us out like termites working through a forest. We remain standing, looking solid from the outside. But the life inside us is gone. We become empty structures, unable to connect with each other because there's nothing left inside to connect with. A forest of hollow trees cannot sustain itself.

My aaji used to say you can tell a tree's health by its fruit. Hollow trees don't fruit. They just stand there, looking like trees, performing treeness, while slowly rotting from the inside. I think about this when I scroll through social media. Millions of people perform humanness. Are we fruiting? Or just standing?

Yes I can think of my thoughts and turn them into a haiku or lyrics. I can take those lyrics, nominate an artist, develop a musical score, and set it to music. All of this seemed easy. Yet as someone who truly enjoys music, I knew it lacked soul.

Yes, I can imagine a frame in my mind and get AI to create the image or photo. But it will not have the story of waking up and climbing atop Mt Ainslie at 5 a.m. in biting frost and making my way to capture the burst of colour in the skies. Or the late-night trip three hours away to photograph the night sky and meteor shower.

The end products lacked the energy of the artist. They didn't tell the story behind them and the journey was absent. The output existed, but the transformation did not. As my thoughts swung between contemplation and conundrum I read an extraordinary news.

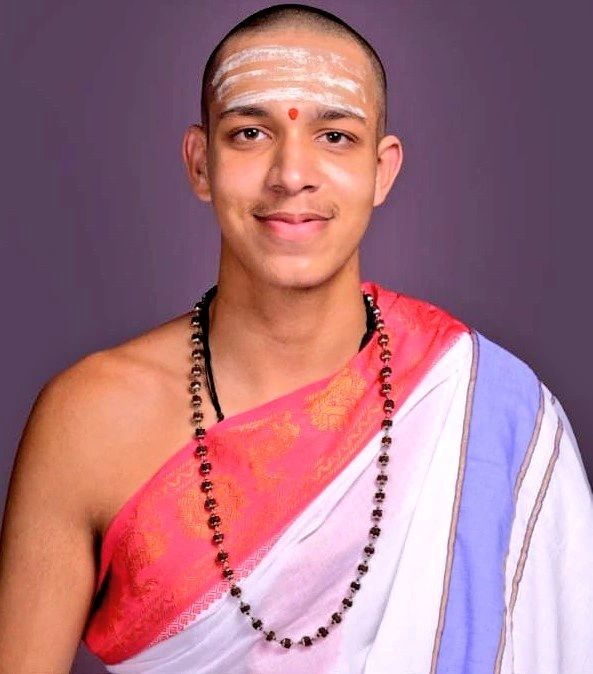

30 November 2025, a 19-year-old named Devavrat Mahesh Rekhe completed something that hadn't been done in nearly 200 years and was only the third time in recorded history. He completed the Dandakrama Parayanam, an incredibly complex form of Vedic recitation. He recited approximately 2,000 mantras from the Shukla Yajurveda's Madhyandini branch flawlessly over 50 uninterrupted days (October 2 to November 30, 2025), totaling around 165 hours of chanting.

He recited them flawlessly without referring to any text. This wasn't done with AI assistance or memory aids or productivity hacks. It was done through the ancient guru-shishya tradition, through years of patient training under his father, through a system designed to cultivate rather than fragment attention. It was a system built on the assumption that human memory, attention, and discipline could be cultivated to extraordinary levels through sustained effort.

The title Vedamurti, 'embodiment of the Vedas,' was conferred on Devavrat Mahesh Rekhe. A well deserved title that demonstrates the merit of sustained, distraction-free concentration that our current systems are systematically dismantling.

So although I enjoyed AI for a brief while, I've realised I still enjoy doing the real thing, hard as it may be. Not because I'm a purist, but because the hard thing is where the meaning lives. The difficulty is not incidental to the value. It is the value.

As I bridge both worlds, I realise that the questions Kosmyna, Russell, Newport, Kingsnorth and other prominent voices raise about depth, meaning, community, and our relationship to the sacred are not new questions. Sanatan philosophies have been wrestling with them for millennia and found tangible, sustainable solutions. Rekhe’s achievement demonstrates that these frameworks still work, that they can produce outcomes our optimisation-obsessed culture has forgotten are even possible. The answers are not merely theoretical. They're embodied in living traditions that have survived the test of time, precisely because they refused to optimise away the difficulty.

Knowing what I know, in 2026, I will scale back on my use of AI. Not to reject AI entirely because I think that jennie is out of the bottle and cannot be put back in; but to use it cautiously and within boundaries set by deeper values.

I will work to rewire my brain and return to both deep work and long thinking. I want to remember what I write. I want to own what I create. I want the stories behind the images, the goosebumps behind the scary and the laughter that makes it funny.

I will write more about how I navigate this dichotomy in a year's time, but for now, I intend to reduce AI to a useful tool and will actively ensure it does not replace my cognitive functions and faculties.

For the record, the outline of this essay, as well as the thinking and connecting the dots, was made by hand, written in pen and paper. It took longer. It was harder. And that, I think, is precisely the point.

Shri Ram and the Feminist Gaze.

Charity, Seva, and the Giving Tree.

The Irrational Fear of Colours.

Resources

- Kosmyna, N., et al. (2025). Your brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of cognitive debt when using an AI assistant for essay writing task [Preprint]. MIT Media Lab. https://www.media.mit.edu/publications/your-brain-on-chatgpt/

- Bartlett, S. (Host). (2025, September 21). I'm quitting using AI as a CEO (and why you should too!) [Video]. In The Diary of a CEO [Podcast episode]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rbS3CLSOeoU

- Bartlett, S. (Host). (2025). An AI Expert Warning: 6 People Are (Quietly) Deciding Humanity’s Future! We Must Act Now! [Video]. In The Diary of a CEO [Podcast episode featuring Stuart Russell]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P7Y-fynYsgE

- Newport, C. (2016). Deep work: Rules for focused success in a distracted world. Grand Central Publishing. https://calnewport.com/deep-work-rules-for-focused-success-in-a-distracted-world/

- Russell, S. (2019). Human compatible: Artificial intelligence and the problem of control. Viking. https://people.eecs.berkeley.edu/~russell/hc.html

- Center for AI Safety. (2023). Statement on AI Risk. Open letter on mitigating extinction risks from AI. https://safe.ai/work/statement-on-ai-risk (Signed by experts including Geoffrey Hinton, Yoshua Bengio, Demis Hassabis, Sam Altman, Dario Amodei, and Stuart Russell, equating AI extinction risks to pandemics and nuclear war.)

- Future of Life Institute. (2025, October 22). Statement on Superintelligence. Open letter calling for a ban on superintelligence development until safety consensus and public buy-in. https://superintelligence-statement.org/ (Signed by around 130,459 people, including Stuart Russell, Geoffrey Hinton, and Richard Branson as of December 2025.)

- Kingsnorth, P. (2025). Against the machine: On the unmaking of humanity. Doubleday. https://www.paulkingsnorth.net/against-machine

- India Today. (2025, December 2). 19-year-old Mahesh Rekhe achieves historic Vedic feat after 200 years. https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/sringeri-blessed-devavrat-rekhe-felicitated-historic-vedic-feat-in-200-years-2829226-2025-12-02

- Holiday, R. (2014, April 1). The notecard system: The key for remembering, organizing and using everything you read. https://ryanholiday.net/the-notecard-system-the-key-for-remembering-organizing-and-using-everything-you-read/

Comments ()